LIVE AID at 40

at Wembley Stadium in London.

Four summers earlier was the last time I had set my alarm clock so early, when I was a quixotic twelve-year-old girl on the morning of July 29, 1981. I had risen before the Midwestern sun to be a live witness (through the television screen) to twenty-year-old Diana Spencer as she became the Princess of Wales and future Queen of England. In the early morning hours of July 13, 1985, I awoke as the same earnest and starry-eyed girl, now sixteen, ever more eager for a live glimpse of Her Royal Highness, Princess Diana, alongside her husband, Prince Charles, and a musician scarcely known to me at the time, Bob Geldof. They greeted the crowd at an event larger than anything my young mind could fathom. The audience expanded vastly beyond the 72,000 tickets sold at Wembley Stadium in London, and the 99,000 at John F. Kennedy Stadium in Philadelphia. From our living room, in our little town, in the middle of rural Missouri, my brother and I were among 1.9 billion people, about 40 percent of the world’s population in 1985, watching 95% of the world’s television sets as the United Kingdom, the United States, Australia, Austria, Canada, Japan, the Soviet Union, West Germany, and Yugoslavia hosted 24 hours of live concerts to raise money for famine relief in Ethiopia.

The lead-up to Live Aid from my view of the world: A lot had changed since that summer of 1981, when I had been a little girl living a middle class, Midwestern American life–experiencing such niceties as central air-conditioning, a comfortable bed, lots of Barbie dolls, and a closet filled with store-bought clothes in a bedroom of my own in a mid-century ranch-style home with a working Dad, stay-at-home Mom, and a little brother. A year later, my brother and I joined the ranks of thousands of other “latchkey kids,” the early 1980s catchphrase for the first generation of Americans to grow up amidst widespread divorce.

In the summer of 1985, I became a licensed driver, opened my first checking account, accepted my first real job in the American workforce–paying taxes, contributing to Social Security, and creating the ability to purchase things for myself like a Sony walkman, albums on cassette, and clothes that didn’t come from a second-hand store. Each weekday morning, I drove my Mom to work at the bank in her 1977 Ford LTD and returned home to care for my little brother. It was a really hot summer, a cruel summer, if you asked me, although Bananarama had affixed that phrase to 1983. At noon, I’d drive the two of us to the city pool for relief during the hottest part of the day until 4:15 p.m. Then, I’d towel my brother and myself off and slide t-shirts and shorts over our wet swimsuits. I placed our damp beach towels on the vinyl bench seats of Mom’s car to prevent our legs from burning as I drove to the bank to pick her up from work.

On Saturday, July 13, 1985, my alarm clock rang extra early, because I just had to view every single, awe-inspiring, musical minute of an all-day global live concert event called Live Aid. I just had to watch a spectacular list of musicians perform live, to save lives. I’d heard about Live Aid through every form of media that existed at the time. The morning and evening news on all three American channels had promoted it for months. Every magazine in the grocery store, from Teen Beat to Time, had Bob Geldof’s face and/or that now-iconic Live Aid logo on its July cover.

Kasey Kasem had talked about it during his weekly syndicated American Top 40 program. Live Aid organizers and The United Nations collaborated with Kasem to create the video clip to be aired throughout the US broadcast on the MTV Network for the purpose of empowering American kids to call 1-800-LIVE AID and pledge their funds to feed the world. These kids had been emboldened by the network from the day they went on the air. On August 1, 1981 their ingenious, controversial, and highly successful promotional campaign began urging kids to call their local cable providers to demand, “I want my MTV!” Most rural American kids could not heed the call of MTV because cable was a fairly new technological innovation which did not reach our towns until the late 1980s. We turned on and tuned in to Live Aid on ABC, CBS, or NBC.

Remarkably, those American networks and magazines, along with BBC across Europe and Australia, and CBC in Canada were able to garner the attention of nearly half of the entire global population. There were also hundreds of radio station DJs talking about it, and record stores and street team kids posting fliers around the world. The fact that anyone could produce anything that could hold the attention of nearly two billion people for 24 hours, leads me to believe that the need to care for humanity led to the most powerful marketing campaign in the history of the world. As someone who produced and promoted hundreds of events in both the pre-digital and the digital age, this concept leaves me awestruck 40 years later.

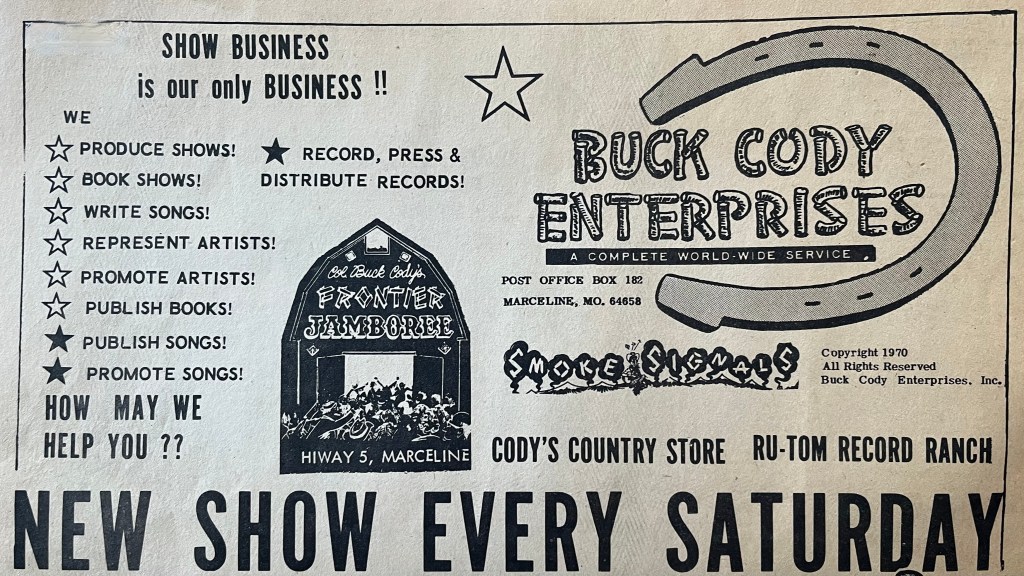

Live Aid was an event I heralded with more anticipation than nearly anything that had come before it in my young life. Mom had always been supportive of my deep affection for music. When I was only three, my obsession with The Jackson 5 resulted in attending my first concert with Mom, in 1972. After that, I was hooked. My grandparents began bringing me along with them nearly every Saturday night to see live music. Right there in our tiny little town, surrounded by majestic treelines and green fields of crops and livestock, was Buck Cody’s Frontier Jamboree. The house band included the classic variety of country music instrumentation–fiddle, guitar, banjo, pedal steel, or ‘steel guitar’ as we called it. For me, a pair of fiddle playing teenage girls were the most captivating element of the ensemble cast. I was spellbound every time as I watched the rapid-fire movements of their bows across the strings of The Green Sisters’ fiddles. Until Live Aid, these events had generated the most visceral memories of my young life. And from these experiences had come an all-consuming desire for my future career. Someday, somehow, some way, I just had to become a part of the glittering world of entertainment.

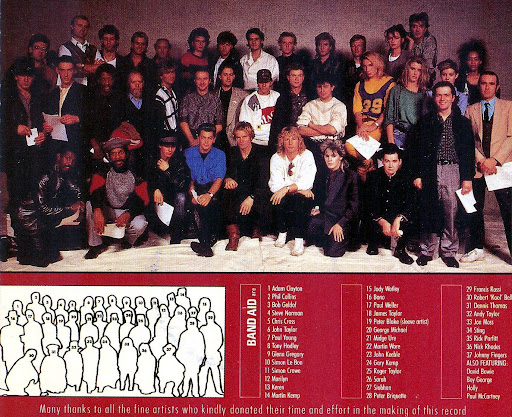

The lead-up to Live Aid from Bob Geldof’s view of the world: In 1984, the frontman for the Irish band The Boomtown Rats had seen a BBC report about a desperate and immediate need in Ethiopia. Hundreds of thousands of people were suffering and thousands were dying every day from starvation, resulting from extreme drought, coupled with corrupt systems in some of the areas affected by the drought. This musician, Bob Geldof, chose to visit Ethiopia and find a way to help. Upon his return, his first call was to friend and Scottish musician, Midge Ure of Ultravox, followed by British pop stars, Sting of The Police and Simon LeBon of Duran Duran. Geldof and Ure recruited 40 European-based musicians to form Band Aid. The single, “Do They Know It’s Christmas?” was recorded on November 25 and pressed on November 26, an unprecedented timeline. The 45RPM record was released on December 7, 1984 and entered the singles chart at number one in the UK and twelve other countries that week. The track sold almost two million copies and raised £8 million ($10 million) in the first eight days.

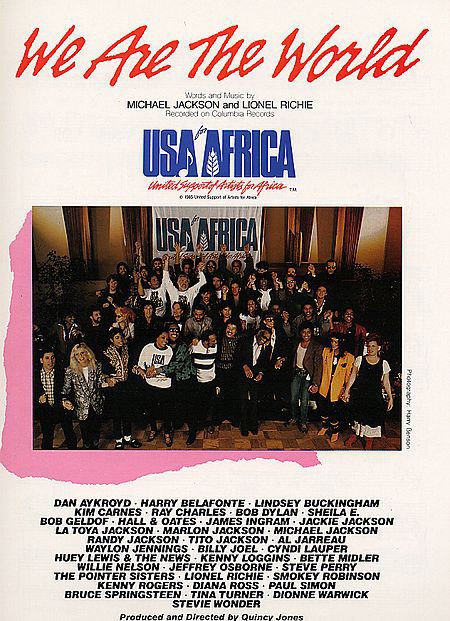

In a recent BBC interview, Geldof says he “was on the phone with Harry” (Belafonte) as the Band Aid Trust was being developed by European music industry legal and fiscal advisor, John Kennedy, who volunteered to create a fund so that all of the money raised would be held in a trust to continually regenerate more funding. Geldof said that once he and Harry started talking, “all the Americans started calling me–Ray Charles, Willie Nelson, Bob Dylan–saying ‘Bob, we want to help!'” Next, Quincy Jones and Michael Jackson set up a meeting with him to talk about “We Are The World.” Jones and Jackson had arranged a plan to record a single featuring all of the top American recording artists in Los Angeles, immediately following the American Music Awards ceremony on January 28, 1985.

This news was the best kind of music to Geldof’s ears, because he had recently met with Margaret Thatcher, Prime Minister of England, who thanked him for his goodwill, but also expressed that his efforts would not be enough to save lives. The need was vastly beyond what eight million pounds could provide and cartels were blocking the aid from getting to the starving people in Ethiopia and other famine stricken countries. Mrs. Thatcher said the problem was too big to get involved. The British government’s unwillingness to provide aid only made Geldof more determined to save people from dying, and it would take more than a temporary Band Aid. A long term plan of action had to be developed immediately. Money needed to be raised to purchase cargo ships, fleets of Range Rovers, and fearless individuals must be recruited to embark across the desert for the secure delivery of food, medical personnel, and supplies necessary to care for and save populations of starving, dying people.

Geldof called the UK’s top concert promoter, Harvey Goldsmith and the two began to formulate the plan for Live Aid. Goldsmith secured Wembley Stadium for the concert, and the two recruited the top concert promoter in the US, Bill Graham. Philadelphia’s mayor called Geldof personally, to donate the use of JFK Stadium. A date was set for July 13, 1985. Eight additional countries, including the Soviet Union, also agreed to organize concerts on that day. Hundreds of live music professionals–managers, publicists, legal representatives, and thousands of production personnel–from all around the globe offered their expertise and talent and time for free. Goldsmith and Graham began securing top tier artists to fulfill Geldof’s request to create a “jukebox bill.” Geldof emphatically expressed to the promoters that ten thousand people a day were dying, Live Aid would need artists who had sold hundreds of millions of records in order to raise hundreds of millions of pounds.

The impact of Live Aid on me in 1985: I mentioned that summer was hot. So hot, that the storm door remained open day and night, so that a box fan could be placed on the floor just inside the front of the house, to churn the outside air from hot to cool, creating a breeze that blew through the living room. Most nights, my brother and I slept on a sheet in front of that fan. We remained affixed in that spot for the entire duration of the Live Aid broadcast.

As the sun was rising in Mid-Missouri, it was high noon in London and the concert began with the arrival of the Prince and Princess of Wales, accompanied by the music of the Royal Coldstream Guard. The fanfare was fascinating, the view of the size of the crowd was astounding. The first band opened with a song called “Rockin’ All Over the World.” I had never heard of the song, nor the artist before that moment. As an American teenager living in a rural town, the wildly popular pop stars of Europe were almost entirely unknown to me then. About ninety minutes and five acts into the event, I recognized a song, “True” by Spandau Ballet.

After a few more acts consisting of more White men with British accents, all unknown to me at the time, a petite black woman with a massive, sleek ponytail, a charismatic presence, and a colossal voice entered the stage. Sade’s three-song set was one of those magical musical moments when everything else around me disappears and I am transfixed by the sound. At a time when popular music was heavily layered with synthesized sound, this woman and her band presented a striking reminder of the immense power of voice and simple instrumentation. I typed and deleted multiple sentences for several days this week, attempting to describe Sade’s performance. Then I realized the only way to convey the experience was to embed the video. There are no words to adequately describe this.

I do wish that I could write that Bryan Ferry, the man who possesses the voice, the face, and the mystique that I admire most in all the world today, gave a performance that captured my heart and mind in an unforgettable manner that day. The truth is that I do not remember his appearance at all. I realized while researching for this essay, that it was on that day when I first heard the lyric which I consider to be the most personally captivating from all of music and of all time.

We’re too young to reason, too grown-up to dream…

I’ve written those words and expressed my interpretations of that line in at least a dozen notebooks throughout the past four decades. But it would be two more summers after Live Aid when those words and this man would first enter my consciousness and remain there forever.

During the Live Aid performance following Ferry’s, I first connected the dots between the voice that uttered the opening line, It’s Christmas-time, there’s no need to be afraid, with the 1985 pop single, “Every Time You Go Away” and the face of Paul Young. As we neared the evening portion of the London broadcast, and the mid-day humidity of Missouri, I was enlivened by what for me, was the most commanding presence of the day. Up until then, the London audience had been engaged, but when a young man dressed in what I would have described as a pirate costume then, entered the stage, the energy changed dramatically. Immediately, 72,000 bodies moved in sync and sang along to every word of “Sunday Bloody Sunday.”

Everything about this band’s sound was so modern, so distinctively different from everything I knew about music. Their performance was raw and aggressive; their presence was alluring and unshakable. Their second song which lasted for twelve minutes and twelve seconds was my first witnessing of live music as activism. The music and the message felt confusing and empowering at the same time. I found myself so moved by the unabashed articulation of 72,000 of my European peers, I was ready to join their movement without actually knowing what their movement was about. I don’t believe that I had any understanding of the conflict in Ireland at that time. After that performance, I found myself wanting to become more culturally aware, more politically active, and more eager than ever before to leave rural life as soon as I possibly could. I just had to experience urban life and other cultures in spaces where I could connect with other creative and empathic souls like mine.

At 12:00 noon Eastern (11:00 a.m. Central Standard Time for me) the American concert began in the City of Brotherly Love. Joan Baez greeted the crowd and opened the show with an a capella rendition of “Amazing Grace.” Our mom had raised us with a reverence for Joan Baez’s stance for social justice and her remarkable vocal style. By this point in the day, Mom had brought lunch to us and taken a seat on the sofa. The three of us, together in our living room on Howe Street, watched music history as it took place live around the globe.

The lineup at JFK Stadium included all of my favorite musicians at that time in my life. The Cars, Madonna, Run DMC, Tina Turner, and Rick Springfield. Even those gorgeous British boys of Duran Duran were on tour in the US at the time, so they too were scheduled to perform on the American stage. At some point in the weeks leading up to Live Aid, I do recall asking my mom how long it would take to to drive to Philadelphia. Her answer was rather vague, yet clear enough for me to understand that it was an outrageous request to make. Nonetheless, at sixteen, it was a little bit heartbreaking to accept that there was no way for me to be a part of that live audience. The bright side of watching Live Aid on television from home was in having the ability to see the entirety of the UK and US concerts, and even a few snippets from some of the other countries.

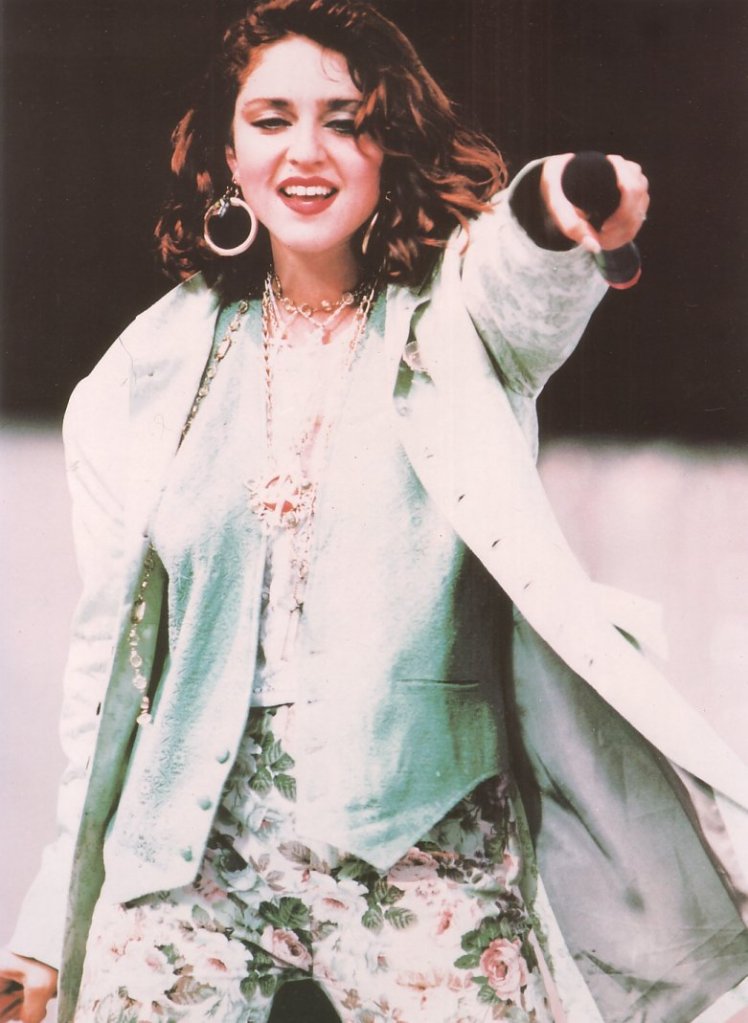

Madonna’s performance of “Holiday” and “Into The Groove” was heralded as one of the most jubilant and joyous setlists of the event. I could not believe my eyes when she skipped gleefully out onto the stage with her natural brunette hair color, it was thrilling. Since first bursting onto the pop music scene in 1983, gutsy teenage girls across the country were bleaching their hair blonde, strategically keeping dark roots, and cutting the sleeves off of t-shirts to ensure their bra straps would show! The Madonna-wanna-be style was an edgy, urban, and unattainable look for a shy Midwestern girl growing up in a place where stepping outside of social norms felt almost blasphemous. At Live Aid, Madonna displayed a whole new style that I could emulate…and I did. Her relatability that day impacted my confidence. Becoming a part of this industry that I so desperately wanted to find a role in, somehow seemed more tangible after that.

The prime time portion of the American broadcast on ABC was hosted by Dick Clark. He guided us through segments from most of the participating countries’ concerts. We saw musicians performing in multiple languages from four continents. Together that evening we watched as British and American artists from Mom’s youth performed with the pop stars of our youth–Hall and Oates with David Ruffin and Eddie Kendricks of The Temptations; and Tina Turner with Mick Jagger. July 13, 1985 was my absolute favorite night ever with my mom and my brother. Mom had purchased a little 3-bedroom bungalow for the three of us in 1982. She worked a minimum wage day job and waited tables on nights and weekends to make ends meet for her single-parent household, but that night, she stayed home with us to watch Live Aid. Although we no longer had the means for such luxuries as air-conditioning, we adored our home on Howe Street. That night, we all three became aware of how incredibly fortunate we were to have our safe and cozy home, clean water to drink, access to a free education, affordable healthcare, and plenty of food in our pantry.

The impact of Live Aid on me since 1985: The mission and the message of Live Aid established a commitment to become more socially aware, and reinforced my impassioned desire to find a career path that would lead me to the music industry without talent for singing, dancing or playing an instrument. After skirting around the edges of a career in entertainment in Los Angeles from the ages of 18 to 21, I returned to Missouri. I could write, and that led me to study journalism in college and to set a goal for becoming a music journalist. I started working in a music venue at the age of 22, as a means of becoming more informed about the inner-workings of the industry. For the next four years, I was developing marketing campaigns to promote concerts at that venue. I spent most of my 26th year on tour with a band from Oklahoma City, and a tour manager who would later become my husband. I finally took a job with a newspaper at age 27, but not as a writer, as director of promotions. In my first year in that role, I developed a budget and plan for a free, one-day, multi-genre music festival at the Will Rogers Theatre in Oklahoma City, and convinced my boss, who then helped me to convince her boss, to greenlight the event. It was a time in Oklahoma’s history when there was a lot of grief and despair in response to the massive loss of life at the Murrah Building that had taken place on April 19, 1995. I wanted to celebrate what was good about Oklahoma, its rich artistic heritage, from its Indigenous roots to Will Rogers to Woody Guthrie, to Garth Brooks, to the Flaming Lips. The Flaming Lips headlined the show, supported by five other Oklahoma-based acts, all representing different genres. My then-husband had served as a tour manager and production manager for many artists, and stepped up to volunteer as production manager for the event. Neither of us requested or received a cent of compensation. It was for the good of our fellow Oklahomans.

A year later, he and I took his eleven-year-old daughter to attend Lilith Fair. There was a warmth and depth to this celebration of female musicians, and a serene absence of the male-dominant angst music of the 1990s. The artist that stood out far above all of the others that day was Sinead O’Connor. I melted into a puddle as she performed her version of Nirvana’s All Apologies. I heard the lyrics of that song in an entirely new way, and was so intensely emoted by the experience that my husband asked me if I was pregnant. The next morning, we were thrilled to discover that our now 26-year-old daughter had also attended Lilith Fair with us that day, in utero…27 years ago this month.

The concepts that Live Aid and Lilith Fair were built upon lingered and percolated inside of me, but I lacked the courage to create a platform for change. Then, at the age of 49, I became friends with a woman half my age who shares the same values and vision as me. My experience had made me resilient and her brilliance made her brave. Together we began to build a business model on two principles:

- to make the music industry a safer and more equitable workplace for women

- to remove barriers that surround public access to live music events–gender, race, income, mobility, and age

We produced a three-day, two-stage, multi-genre, mulit-generational live music festival that featured 27 touring artists, including headliners Brandi Carlile, Sheryl Crow, and Mavis Staples. Every act in every slot in our lineup was led by a woman artist. Nearly 8,000 people were able to access the event because we made it as affordable, accessible, and safe as we possibly could.

Privately, behind the scenes in the months leading up and during every moment of the event, we were being personally threatened and harassed. We worked closely with law enforcement and we spent tens of thousands of dollars on professional event security to ensure the safety of everyone on site. Equity and safety come at a high cost these days. In the year that followed, we garnered national media attention lauding our event, and received accolades for our work at music industry events held at the Beverly Hilton in Los Angeles and at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland. The country was just beginning to recover from the staggering number of lives lost, and to assess the massive financial loss caused by the pandemic. Locally, we lost sponsorships, and no one that we asked was willing to make the long-term investment we needed to help us get back on our feet. Production costs skyrocketed, but we hung on another year and produced a second, highly diverse, well-attended, but under-funded event. Some local media shared untrue and unkind things about us when we came to the heartbreaking conclusion that it was not financially sound to continue. Again, people who didn’t even know us were sending threatening messages to us. I no longer felt safe in the community where I had lived for 35 years. Most of what we went through we will keep to ourselves forever because the good that we were able to do by taking a stand for social justice will always be more important than the hardships we endured.

The impact of Live Aid on the world since 1985: There is a legitimate argument to consider about the long-term misconceptions about Africa and its people, caused at least in part, by the earnest efforts of Live Aid. In 2023, Moky Makura, executive director of Africa No Filter wrote, “Sadly, the mainstream media, the most influential ambassador for the Live Aid legacy, still largely perpetuates this dominant narrative about a broken continent plagued by poverty, conflict, corruption, crime, poor leaders and disease. In their version of Africa, the continent is a place beset by dependency and full of people who lack agency.” The full article from The Guardian is available to read here: “Live Aid led to the patronising ‘Save Africa’ industry.”

In a recent interview with the BBC commemorating the 40th anniversary of Live Aid, Geldof discussed his own reservation about screening a newsreel during the concert at Wembley, that had been produced by the Canadian Broadcasting Company in 1984. He described the piece as “the pornography of poverty” and discouraged its use during the concert, because, he felt there was “no need for human degradation” in order to move people to support the cause. He cites David Bowie as the catalyst for the ultimate decision to show it on screen that day. In their planning for the event, Geldof eventually bent to Bowie’s will. Bowie introduced the short film to the London audience following his set, and it was included in the live broadcast on BBC that day. As it turned out, this was indeed the time in the day when “all the phones rang across the world.” Everyone, whether in the crowd at Wembley or “at home watching the telly” immediately understood the immediacy of the need to relieve the human suffering that was happening live in that moment. The videographer who shot the footage did not leave anything to be imagined about the situation in Ethiopia. Just as Bob Geldof had witnessed in person, thousands of people were dying, and children’s tiny bodies wrapped in gauze for burial were all around him. The newsreel can be found on youtube.com and should be viewed only with compassion and the ability to understand the intended purpose of its content. One living example of that intended purpose is Birhan Woldu. An Ethiopian woman who was seen as a young girl pronounced by a nurse as being on the verge of death in the CDC newsreel. But Woldu survived, and lived to tell the story of how Live Aid saved her. She has become a political activist, philanthropist and teacher who has attributed her life to Geldof.

The complexity of what was happening and the reason why it was happening was utterly and completely consuming to me as a 16-year-old in 1985. Nonetheless, as a 56-year-old who has studied journalism and marketing, and spent decades working in the live music industry, I paused after writing the previous sentence, made some breakfast, went to church, and thought about those words and the world we live in today. Although there were far fewer ways to connect and communicate forty years ago, it was possible to deliver one true, authentic message, nearly impossible to misconstrue. At that time, billions of people were caring, willing, and trusting of a singular directive, and contributed to fund humanitarian aid, if they had any means at all to do so. I don’t think that will ever happen again. In 1985, we did not hesitate to call 1-800-LIVE AID, when the message appeared across our television screen. We wanted to be a part of this genuine global goodwill cause, as did millions of other people who donated that day.

The onslaught of digital media in the 21st century has splintered into millions of streams of communication that can connect humans instantly, all over the world…so much of it, so compelling, yet entirely untrue. It seems that technological advances have divided our species into two types of humans, the cautious and caring or the manipulative and greedy.

Geldof has been criticized and scrutinized endlessly since 1985. From all of the research I have done, my conclusion is that his message to the promoters, volunteers, artists, fans, and donors of Live Aid was and is clear and direct. He has never wavered from the goal of raising hundreds of millions of funds to feed hundreds of millions of people. Since December of 1984, The Band Aid Charitable Trust has raised and spent more than £145 million ($150 million) to provide food, medicine, housing, hospitals, water, infrastructure, schools, and educational materials directly to those in need. With no paid staff and no offices, the Trust continues to offer its assistance to the human need that Geldof brought to the world’s attention on July 13, 1985. To learn how you can become a part of the movement, visit: The Band Aid Charitable Trust