On August 8, 2020, I wrote this Note from the Listening Gallery to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the release of the film, XANADU: https://thelisteninggallery.com/2020/08/08/building-your-dream-has-to-start-now-theres-no-other-road-to-take/

Five years ago, Olivia Newton-John was alive. Jeff Lynne, songwriter, vocalist, and founder of Electric Light Orchestra was healthy and on my bucket list of beloved artists yet to see live in concert. My daughter and I were tucked away in our cozy little home, hoping to remain safe from the deadliest pandemic in a century. Today, a day late because I had so very much to say that it took an extra day to edit this tribute down to a readable length, I honor the memory of Olivia Newton-John on the third anniversary of her passing, and the 45th anniversary of the release of Xanadu with an updated Note on my affection for the film, Olivia, ELO, and their everlasting and ever-evolving influence upon my life.

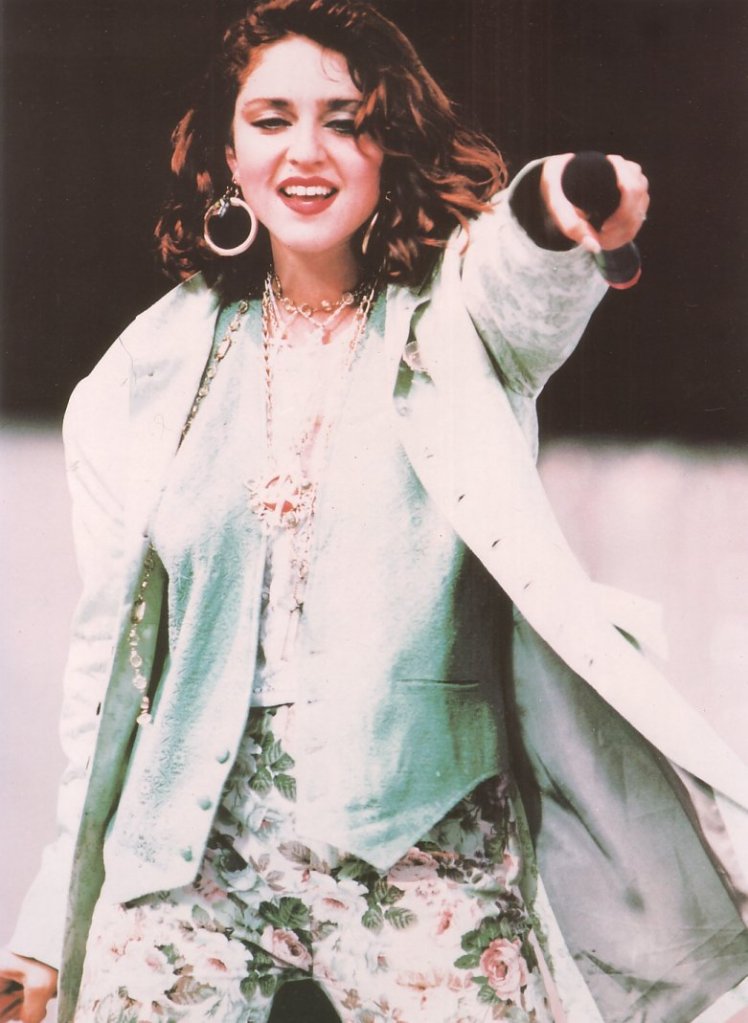

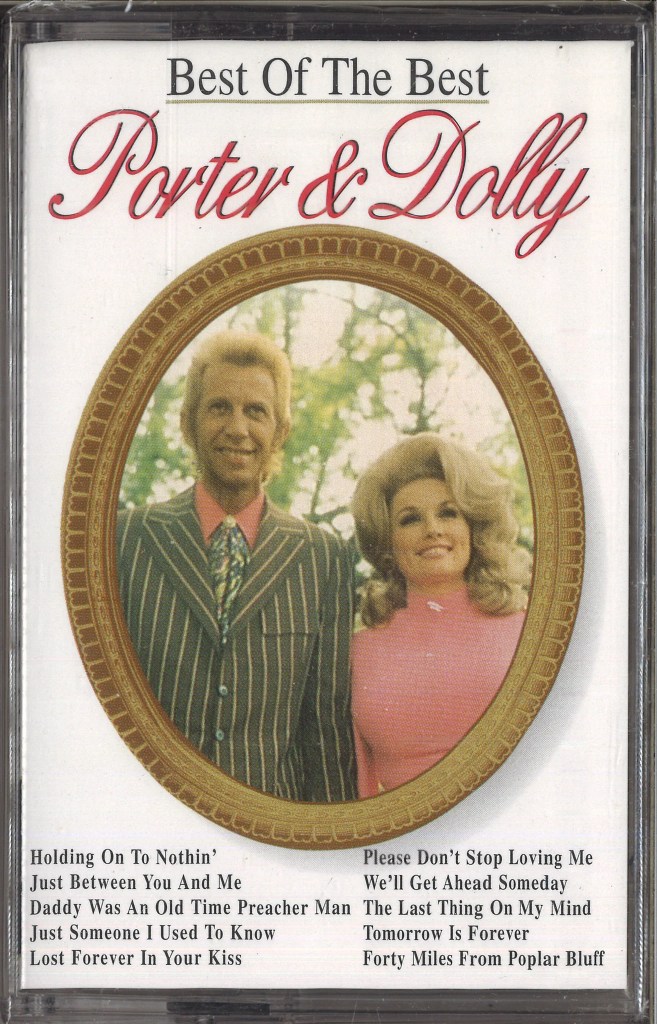

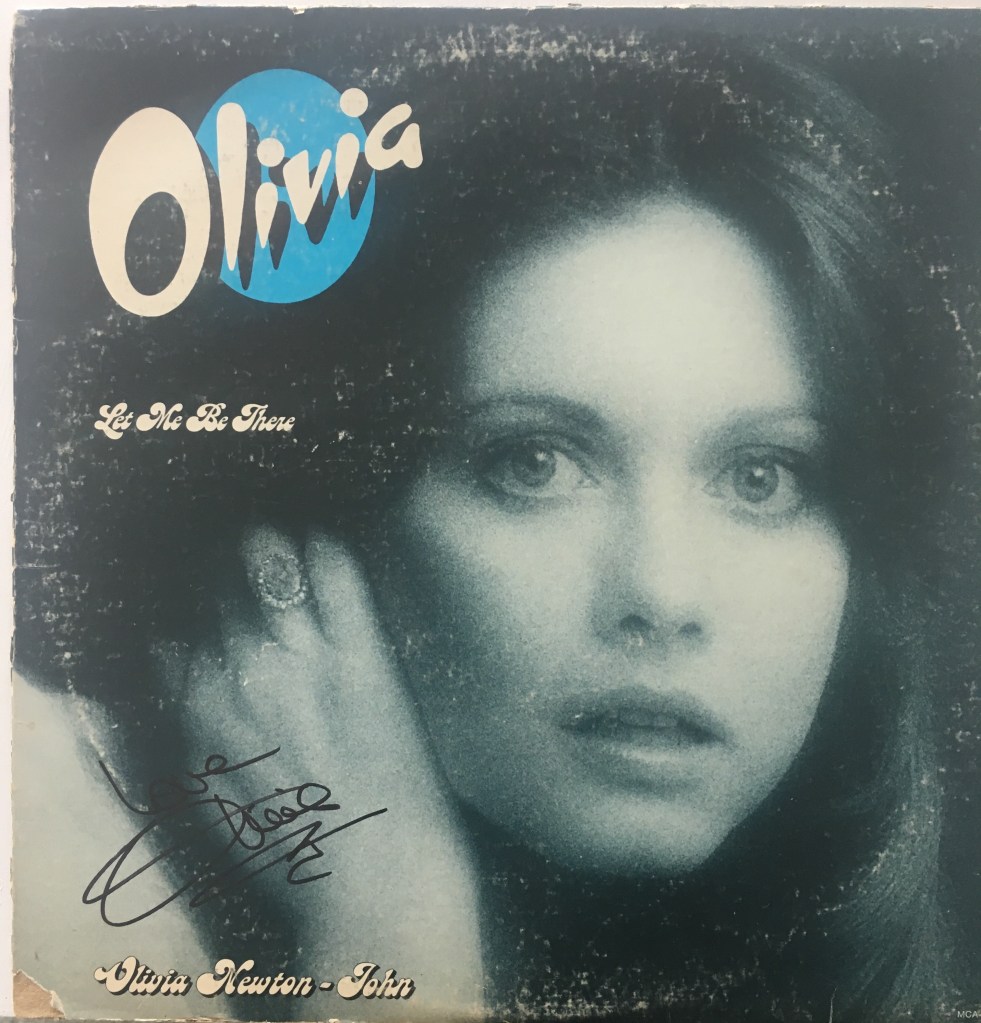

Olivia Newton John’s presence in my life: I have admired Olivia and her music since I was four years old, when her American breakthrough album and single Let Me Be There dominated the country charts in 1973. Her talent was recognized by the Country Music Association, by awarding her with the 1974 Best Female Performer title over fellow nominees including Dolly Parton, Loretta Lynn, and Tanya Tucker. Between 1973 and 1977, Olivia released fifteen singles, ten of those reached number one on the country and/or pop charts. In that same timeframe, she released seven top-ten country albums. For 45 years, Olivia held the Guinness World Record for the shortest gap of just 154 days between new number one albums by a female artist on the US Billboard album charts with If You Love Me, Let Me Know and Have You Never Been Mellow until 2020 when Taylor Swift achieved two number one albums in 140 days. In 1978, Olivia appeared in her first American feature film, an adaptation of the Broadway musical, Grease, and became the number one most influential artist in my life. Two years later, she was cinematically immortalized as one of the nine daughters of Zeus in the musical fantasy film, Xanadu.

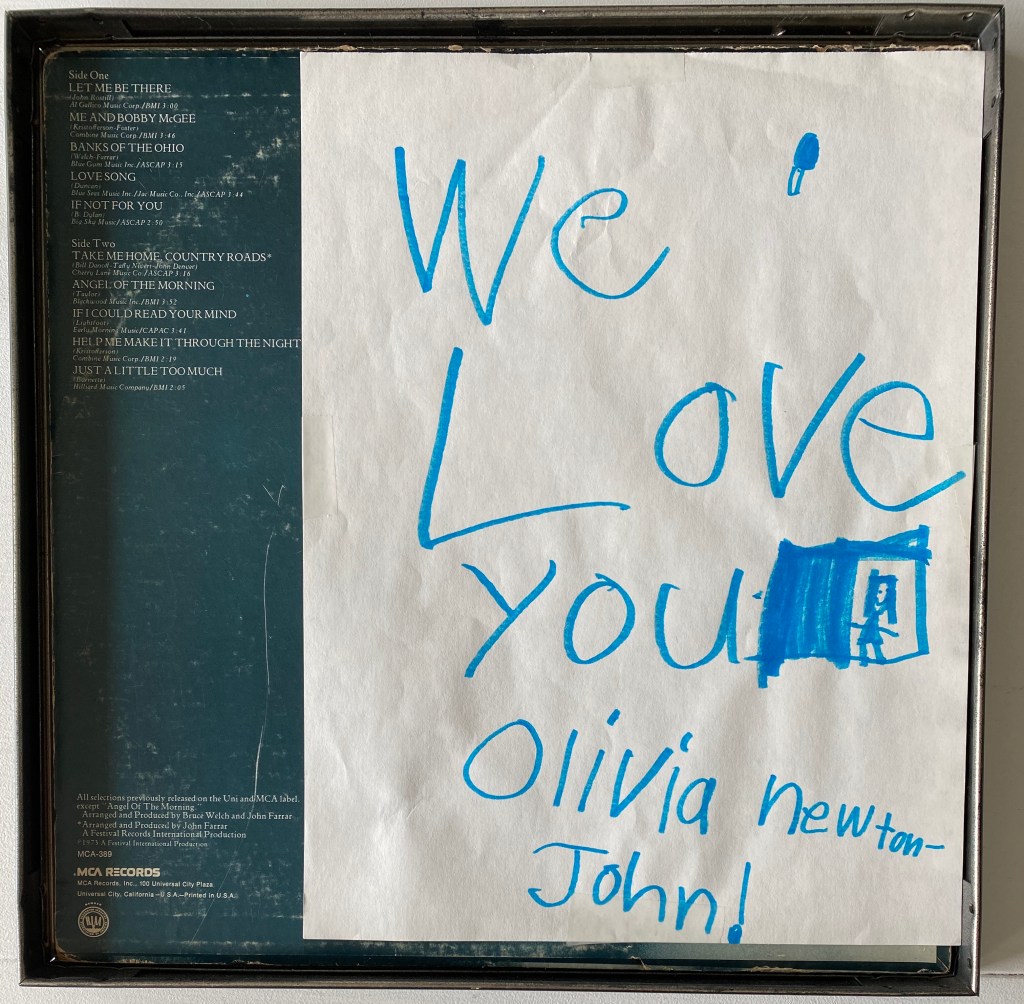

Olivia’s deeply principled and remarkably generous philanthropic work for the health of the Earth and all life on it are the reasons why I have continued to admire her throughout my adult life. In 2006, I had the profoundly fortunate opportunity to meet her when she performed in the small city where I resided for 35 years. She was exactly as I had always imagined her to be, gracious and genuine. Backstage, after the show, she talked with me as if I had been a part of her history as much as she had been a part of mine. She signed my Grease poster from 1978 and my Let Me Be There album from 1973. I presented her with a gift from my seven-year-old daughter, the drawing below. Tears formed in the corners of Olivia’s eyes. She shared that she too had just one little girl, and her little girl was all grown up now, and she loved her so dearly that she could not accept my daughter’s drawing. She explained that one day, that piece of paper would mean far more to me than I could possibly know that day, and she asked me to save it and treasure it. I heeded her advice and tucked it inside of my autographed album. Upon Olivia’s passing, my daughter was “all grown up.” I told her the story and revealed the treasure inside of the album that had been framed on our living room wall for sixteen years. I placed the record on our turntable. Tears streamed from my eyes as we sang along to every track and I experienced the unmatched joy of hearing the pops and crackles exactly as I had heard them 40 years earlier.

In 2022, one month after Olivia departed from this world, I traveled to Los Angeles to pay proper tribute alongside my dearest friend from my years of living there–the one who first took me to the majestic rocks of Point Dume at Zuma Beach in Malibu, the spot from which Gene Kelly’s character first appears in Xanadu. She and I lunched at the beach that day and reminisced about Olivia–she and my friend had once been neighbors in Malibu. We cut flowers from my friend’s garden and delivered them to Olivia’s star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. And of course, we listened to the Xanadu soundtrack as we travelled down Sunset from the beach to Hollywood.

Jeff Lynne & Electric Light Orchestra’s presence in my life: I was absolutely spellbound from the very first time I heard Electric Light Orchestra’s “Strange Magic” in 1975 at Topp Cats Roller Rink.That classically arranged string intro so gracefully segued into a typical mid-1970s voice and guitar ballad piece, and then, WOW! All sorts of soaring, sonic sounds, unlike anything I had ever heard before, rushed in to join the strings and guitar to reach a stirring crescendo. Fifty years later, as I listen to this song, I recall the heady experience of the rink floor rapidly moving under me. I feel the muscle memory of the pivot in my feet. I am lifted—body, mind, and spirit…strange magic, indeed. The elegant and haunting “One Summer Dream” also from 1975’s Face the Music album, is how I began to crave the sensation of feeling music in a physical way. Whenever I heard that gorgeous string arrangement intro over the PA system, I would skate over to the corner to sit directly under the speaker mounted there and place my back against the wall to intensify the sensation of music pulsing through me. Previous to discovering ELO at the local roller rink during the summer of my sixth year of life, my musical tastes had been formed from listening to the records purchased by the adults in my family or from watching an artist on television with them. Because of my experience at Topp Cats, I have a deeply personal connection with Jeff Lynne’s Electric Light Orchestra as the first band to be my band, a musical discovery all my own.

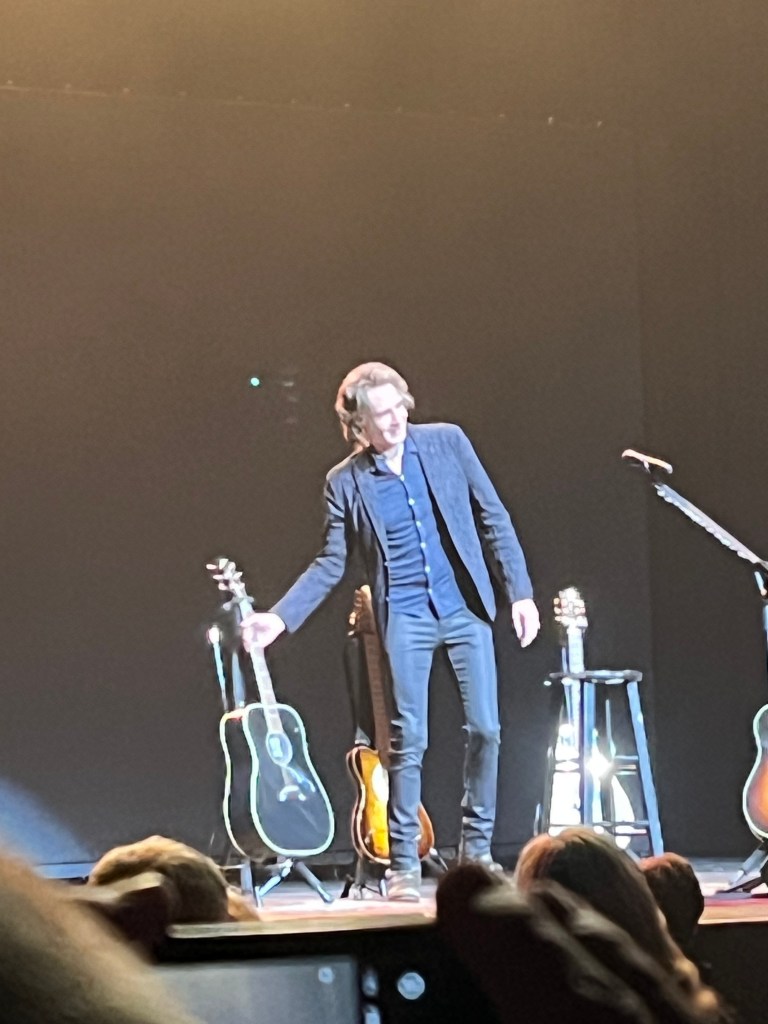

Just ten months ago, my hometown bestie and I experienced the live magic of Electric Light Orchestra together. Throughout the past few decades, the two of us had been separated by the inevitable circumstances of adult life–jobs, families, and miles. Then last year, I returned to my hometown to press the restart button on my life. One of the very best aspects of this move has been the fact that she and I could reconnect as if the past 38 years were only a small moment in time. She and I first bonded in our preschool Sunday school class at our hometown Methodist church more than fifty years ago. As it turns out, those shared spiritual roots have proven the test of time, as we have discovered that we still share the same values. We also still share the same reverence for music and musicians that we shared at Topp Cats Roller Rink, where we first experienced ELO in 1975. Below is a video from their concert we attended together, a performance of “All Over the World.” Their “Over and Out” tour began last summer and was scheduled to end last month. Jeff Lynne’s declining health near the end of the year-long tour resulted in the cancellation of the final two shows that were set to take place a few weeks ago. Lynne has released a statement that he is unable to perform any longer and those two shows will not be rescheduled.

The impact of XANADU on my life: Nothing could have been more magical for a dreamy eleven-year-old country girl than a musical fantasy feature film starring Olivia Newton-John with a soundtrack from my favorite female vocalist AND my favorite band. On opening day, August 8, 1980, my mom drove my brother and me to Kansas City to see the film I had been eagerly awaiting all summer long. That three-hour car ride from our rural home-town to the city, was the final step in my three-month anticipation for the release of this film. We went to the theater in a district of Kansas City known as The Plaza, a beautiful and romantic area designed to replicate Seville, Spain. Dozens of gorgeous fountains and sculptures adorn fifteen blocks of shops and restaurants housed in Spanish-inspired architecture. There could not have been a more inspired setting in my home state for me to see Xanadu for the first time.

Xanadu did not disappoint. Not me, anyway. The critics, however, had a very different opinion of this musical love story on roller skates that featured multiple over-the-top fantastical dance scenes that merged the electric sounds of the 1980s with 1940s big band music. First, we meet Danny, an elegant elder musician, biding his time by wistfully playing his clarinet on the beach near his Malibu mansion. Next, we are introduced to Sonny, a young man with big dreams, working an uninspiring job for a music label, painting replicas of album covers to be installed outside of Tower Records on Sunset Boulevard. Next, the nine daughters of Zeus are brought to life from a mural on the Venice Beach Boardwalk. This is where we first see Kira, the roller-skating muse, portrayed by Olivia Newton-John, sent by Zeus to inspire the two men. Her sisters are a multi-racial ensemble of goddesses, a boldly inclusive depiction for 1980 cinema.

Upon removing herself from the boardwalk mural, Kira roller skates up the city’s coast from Venice Beach to Zuma Beach, on a muse mission to bring the young idealistic man and the older seasoned music industry professional together. Both are disgruntled by the industry for different reasons, yet share an unyielding passion for music and creativity. Kira leads them to the once illustrious, but now decaying architectural icon, the Pan Pacific Auditorium. Once Kira has lured the two men to meet in the venue, she recites Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s 1797 poem about Xanadu. Magic ensues, and in the final scene, Kubla Khan’s empirical palace built in 1256 China, is reborn as roller-disco-meets-big-band-nightclub in the Los Angeles Inland Empire.

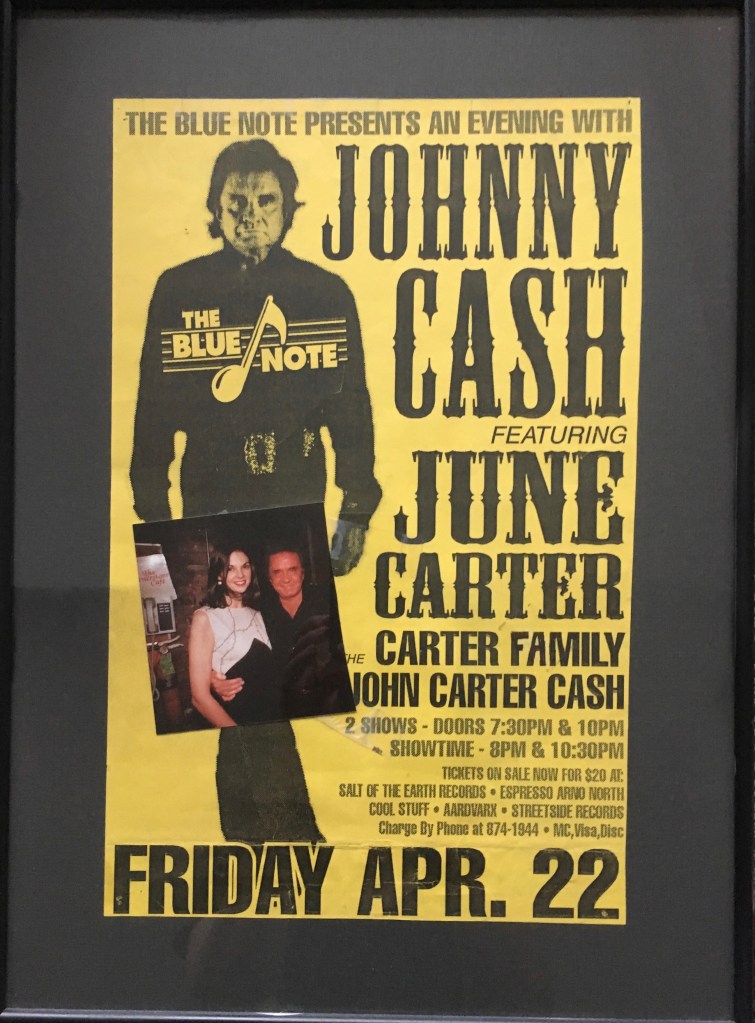

May 24, 1989.

Nearly every scene in the 96-minute film includes a magnificent dance routine on the scale of 1940s MGM musicals, all choreographed by Kenny Ortega, now a legend in the industry to nearly the entirety of America’s Gen Z young adults, because of his work in Disney’s High School Musical franchise. Then, there is the astounding fact that the elder music man’s role is played by none other than the brilliant Gene Kelly. His role as nightclub owner, Danny McGuire, from his 1944 film Cover Girl is reprised in Xanadu, which turned out to be his final film. His genuinely legendary dance technique and personal style are artfully and reverently presented, yet modernized for Generation X in a scene set in the uber-trendy 1980s Beverly Hills boutique, Fiorucci. The song for this fantastical dance number is “All Over the World” my personal favorite ELO track from the soundtrack. Though I’ve often said I cannot cite one ELO track as my all-time favorite, because so many are so beloved, this one is certainly a contender. If you do not watch any of the other clips embedded in this essay, I implore you to watch this one fully, to take in all of the splendor and excess of the 1980s at its very best and to witness the absolute genius and bona fide charm of Gene Kelly. Then imagine what this must have felt like for this eleven-year-old farm girl to witness on the big screen. There are no words to convey my level of adulation, awe, and intense longing to become a part of the music business at that time in my life.

The final scenes of Xanadu include an impassioned conversation somewhere in the Heavens between Kira’s love interest, Sonny, (the young ingenue) and her parents, Zeus and Hera. His desire to keep his muse in his world is so intense that he roller rams himself into the wall on the boardwalk where Kira’s image is depicted alongside her sisters. The closing number is so extravagant, Gene Kelly even roller dances, amidst a corps of jugglers, fire-eaters, acrobats, skaters, and dancers from multiple cultures and races, genders, and what was most likely my first witnessing of gender fluid representation.

All of this unfolded on what was likely the largest cinematic screen I had experienced at that time in my life, as well as a breathtaking showcase of Los Angeles culture with its beaches, palm trees, and stunning art-deco architecture. What’s not to love when you’re a pre-teen farmer’s daughter who has lived inside her fantasy of becoming a part of the entertainment business since she could walk and talk? I was captivated by every aspect of this film.

I had to embellish my own style a bit to emulate my new screen heroine, Zeus’s dancing, singing and most importantly, roller-skating, daughter. I adorned my white roller skates with shiny silver sticker letters bearing my initials “TNL” on the back spine of each skate under my newly purchased leg warmers. I also dressed in frilly peasant blouses and flowing prairie skirts in pastel colors. I wrapped long flowing ribbons into my barrettes, just like Kira’s, and I even draped nine of my grandma’s silky scarves from an elastic belt around my waist, in my effort to replicate and represent the nine muses’ fluttering layered dresses. Then, I floated around the rink floor at Topp Cats in this attire. Yep, seriously, I did that. At home, I stood in front of my bedroom mirror and attempted to replicate that fabulous Ortega choreography. I was particularly captivated by the number during which Kira magically transforms her visual appearance and musical style from 1940s siren, to 1980s punk, to rhinestone cowgirl, in a three-minute song titled Fool Country, which is not included on the soundtrack album, but appeared as a B-side of the “Magic” 45RPM single.

Since I was three years old, I had wanted to become a dancer, or singer, or literally anything that would connect me to the glamour of some sort of music-related career. Until Xanadu, nearly all of my favorite media had allowed me glimpses inside New York’s entertainment industry and/or New York City itself–Funny Girl, That Girl, The Goodbye Girl, Mahogany, Annie, The Wiz and Breakfast at Tiffany’s. Xanadu was my first exposure to Los Angeles, and instantly, I was enamored. My fascination for NY was magically transported to LA. The awareness of Los Angeles as a launching point for my future career could be somewhat tethered in reality, and that concept became obsessively compelling for me. I had a great aunt and uncle who lived in Los Angeles, and perhaps one day I could go and visit them there. Seven years after seeing Xanadu, I would do just that.

By the late 1980s, a number of young women had been declared supermodels due to their appearances in rock music videos since the onset of MTV in 1981. A career as a fashion model became my plan for a role in the music industry. I had the height and the commercially determined physical attributes required for the job, and despite my most earnest efforts to acquire the skills of a professional dancer throughout my childhood, I lacked the talent.

During my first week in Los Angeles, by pure chance, my friend took me to Zuma Beach to witness for the first time, the beauty of the sun as it melts into the Pacific Ocean at dusk. That experience from 38 years ago lives in my mind and heart as if it happened last night. Not only was I spellbound by the majesty of the ocean, but at the realization that I was in the place where Gene Kelly had played his clarinet in the opening scene of Xanadu. My favorite photoshoot during my brief career in Los Angeles took place on those same rocks. Thirty summers later, I photographed my daughter in that same spot at Zuma, to ensure her dreams would one day come true as well, because I still consider Zuma Beach in Malibu to be the most magical place in the world. I try to make a pilgrimage to those rocks, to be suspended in time in my zen zone, every time I visit the glittering city of the angels. Zuma is my connection to that eleven-year-old farm girl inside of me who believed her dreams could come true at the beginning of the 1980s, as well as to that eighteen-year-old girl in me, who actually got a shot at making her dreams come true in Los Angeles at the end of the 1980s.

The eternal magic of Xanadu:

Magic was the first single from the forthcoming album. The track was released during the week of my eleventh birthday which of course, I considered not at all coincidental, but rather, purely magical. The song remained at number one on the pop charts for four weeks that summer. I was absolutely enchanted and wholeheartedly believed in the magic of those lyrics. In 1980, every word of that ethereal and intriguing song resonated with a message that inspired me to keep dreaming until I found my rightful place in the entertainment world, in some glittering and glamorous city, far away from my rural home. I wrote the lyrics again and again in my notes throughout the next few years of my life, and examined their meaning again and again, making promises to myself to keep all my hopes alive, so that my destiny would arrive.

Throughout the four decades since first hearing them, my belief in those lyrics we have to believe we are magic, nothing can stand in our way, has ebbed and flowed. Today, on the 45th anniversary of Xanadu, after five years of what sometimes feels like merciless challenge for me, and an awareness of the unprecedented hardships and loss for so many people in this world, we could all use a little bit of magic. We have to believe we are magic…we don’t have to be kissed by a muse to be inspired. Every one of us has the human ability to inspire others through compassion, kindness and empathy. Let’s be better humans, to our world and to all humans all over the world.

Magic served as the perfect sentiment to honor Olivia’s profound impact on my life and my daughter’s when Olivia left this world. In response to my grief, it was my daughter who suggested that we imprint a bit of Kira’s musing, lyrical, and magical prophecy on our arms so that forever onward, in moments of doubt, we can simply look upon ourselves and be reminded.

you won’t make a mistake

i’ll be guiding you