by Tracy Lane

Heart Like a Wheel is an album of historic note, so much so, that the Library of Congress catalogued it in the National Recording Registry in 2013, as one of the most important audio recordings in American history. This album also passses my own rigorous criteria as a perfect album of 20th century American music, a classification I’ve cited for a scant few records. Heart Like a Wheel is ranked between Stevie Wonder’s Songs in the Key of Life (number one) and Mazzy Star’s She Hangs Brightly (number three) on my list of albums that I regard as recordings of seamless perfection. In this Note, I endeavor to share with you why Linda Ronstadt is integral to our shared American culture, and why this album which turns fifty today, stands out among her discography as critically important, as well as personally beloved.

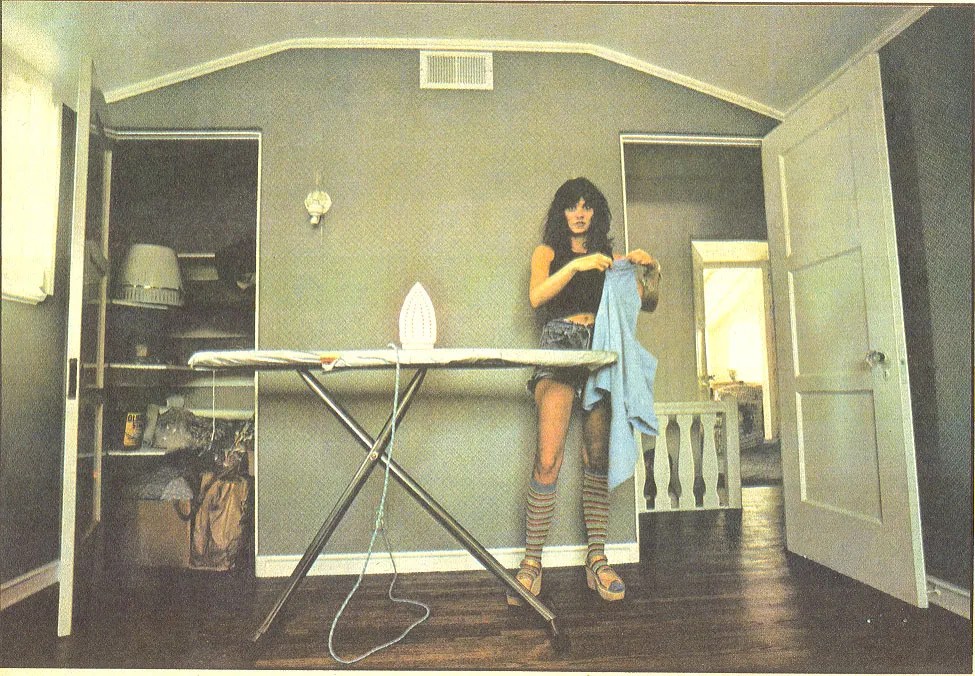

Heart Like a Wheel was released on November 19, 1974. The album transformed Linda Ronstadt’s life from that of a folk singer playing the club circuit to the first female rock musician to sell out an arena tour. In her 2013 memoir, Simple Dreams, she reveals that while making this album, her greatest hope was “to earn enough money from making music to purchase a washing machine.” Heart Like a Wheel soared to the number one position on both the pop and country Billboard album charts and remained on the charts for 51 consecutive weeks. The album received four Grammy nominations, including Album of the Year. In her autobiography, Ronstadt credits the popularity of this album for giving her the ability to purchase the home that provided the serenity and privacy vital to keeping her mind and body healthy and free from the tribulations of the touring life, which many of her Angeleno companions fell victim to when stardom entered their lives in the mid-1970s. Cameron Crowe and Annie Leibovitz came to visit Linda Ronstadt in her new home for a 1976 cover story in Rolling Stone. The spread revealed that the album’s sales and subsequent tour proceeds provided her with the funds to purchase her first washing machine, her first piano, a beautiful blue paisley sofa, and her first home of her own–a sprawling, yet cozy, beachfront home in the gated Malibu Colony community.

To trace the spark for my reverence of Linda Ronstadt, I have to go back a few years prior to Heart Like a Wheel, to 1967, two years before my existence. Mom and Linda were both twenty years old when The Stone Poneys’ pop single “Different Drum” became the first track featuring Ronstadt’s inimitable voice to appear on the Billboard charts and on the turntable in my Mom’s college apartment. During the first four years of my life, that single would be placed in our family’s communal stack of 45RPM singles in the cabinet inset between two speakers swathed with orange velveteen fabric and a groovy swirling pattern of maple wood on either end of my grandparents’ console stereo. Music was essential to everything that took place in that home on Gracia Street where I lived with my mom, aunt, and grandparents. All day long, as the women in our home went about their day, music poured out of that glorious wooden box in our kitchen and streamed throughout the house and into the auditory tracks of my young mind. My aunt was in high school when I was born, exposing me to a palette of late 1960s and early 1970s rock and roll on that stereo. Mom wrapped us up in a soft and gentle tapestry of folk-rock and soul-infused sound capsules that filled our home with hope as our family mourned the losses of the civil rights leaders who had been murdered in the year before my birth, while also praying for brothers, uncles, cousins, boyfriends, and best friends sent into brutal conflict on the other side of the world. Country was Grandma’s genre of choice. I sang along with her and Loretta, and Dolly, and Tammy, about the challenges of everyday life for the American woman while Grandma cooked and cleaned and cared for her family. When Grandpa came through the back door in the evenings, he’d place an old honky-tonk record on the turntable, most often a tune from his favorite musician, Hank Williams. Then he’d take Grandma in his arms for a quick spin around the kitchen before supper. In the documentary film, Linda Ronstadt: The Sound of my Voice, she describes a childhood household quite like mine. “All kinds of music played in that house…Music was incorporated into everything we did…We sang with our hands in the dishwater.”

Listening to music was no longer a household family affair when Mom and I moved from the home we shared with her parents and younger sister to an apartment we shared with Mom’s only husband, the only man I have ever regarded as Dad. The family’s console stereo remained in my grandparents’ home and Mom bought a ‘kiddie’ stereo for me. It was one of those particle board box models that folded and latched like a little suitcase. For the first time, I had a bedroom of my own, the only room where music played in that apartment. I listened to Mom’s copy of “Different Drum” as well as Ronstadt’s 1970 solo single, “Long, Long Time,” and claimed them as ‘mine.’ I kept my favorites from Mom’s collection of 45s on a spiraling wire shelf at the bottom of my record stand.

At the release of Heart Like A Wheel in November of 1974, Mom and Linda were 27-year-old women with aligned values, despite remarkably different environments. Mom was a married mother of two and a card-carrying member of the newly formed institution, National Organization for Women, representing a tiny sliver of rural Midwestern women willing to openly support the ERA at that time. Linda Ronstadt was becoming known as an artist willing to call out misogyny as she saw it in Los Angeles, the center of the recording industry in those years. In an interview from the mid-1970s she is quoted as saying: “The rock and roll industry is dominated by men…there’s a real hostility against women.“

I was a five-year-old country girl who looked up to both of these women, with a deep passion for nearly every genre of American music and a burning desire to become a part of the music industry. Heart Like A Wheel spoke to me in a language beyond my intellectual capacity. I simply understood that every single track evoked a sense of belonging in me–whether it was folk, country, rock, pop, or R&B–these ten songs reverberated through me with a piercing depth that has endured, expanded, and evolved through the past fifty years.

For several years, I’ve wanted to write an essay about Linda Ronstadt’s impact on American culture, but have held back, for fear of not getting it right enough. In 2019, Dolly Parton, who collaborated with her and EmmyLou Harris on the Trio albums, described Ronstadt’s unparallelled propensity to embrace a songwriter’s work in such a way that her listeners feel she absolutely wrote any song she decides to sing: “She gets inside it. She becomes it.” For as long as I can remember, I have been moved by certain songs that emote me in such a way that I cannot stop them from playing on repeat in my brain for days or even weeks at a time. In 1991, in reference to my favorite album at the time, I wrote in my journal, “I want to BE inside this music.”

Linda Ronstadt is not a songwriter, but she has the innate ability to love a song so personally that it becomes a part of her and a vocal range that could champion every genre, and she did exactly that, fearlessly and flawlessly. She can rearrange a song endlessly in her mind until it adequately expresses her passion for the song. In the aforementioned documentary film, she attempts to explain this trait as somewhat of a compulsive desire. “I’ll have to sing it. I’ll just burn to sing it.” I understand that devotion, but I do not possess the talent to craft a song into my own rendering of it, nor to sing it. My compulsion is expressed through the composition of flowering prose to articulate the relationship between beloved songs and me. My hope for every Note I write, is that if you do not yet have an appreciation for an artist or album I write about, after reading my Note, you will. Below, I share the history and nuances of each track on this stunning album to illustrate why every song on Heart Like a Wheel is an integral piece of our shared cultural history and a sacred memento of my life.

Track 1: “You’re No Good” is an R&B song first recorded by DeeDee Warrick, but Ronstadt has stated that it was when she first heard Betty Everett’s 1963 arrangement that she became so obsessed with the song that she “couldn’t not sing it.” Ronstadt’s fondness for the track resulted in her first number one single on The Billboard Hot 100 chart. Ronstadt’s rendition opens the album with a powerful downbeat and a throaty rock and roll vocal style, immediately delivering a message that Linda Ronstadt has a range that she had not previously exhibited and she is ready to revel in it on this record.

Track 2: “It Doesn’t Matter Anymore” is the song I recall as my favorite track from the album at the time of its release. Ronstadt crafted a heartbreaking country ballad from a sweet and swift-paced pop tune first released in 1956 by Buddy Holly and the Crickets. Country music was the genre most familiar to me during my earliest years of life when we had lived with Grandma and Grandpa. So, it is only natural that Ronstadt’s arrangement, with its grieving lyrics throughout and that mournful pedal steel solo midway through the track, would serve as a melancholic reminder of home for me when it was released in 1974. This song also served as the most healing elixir for the pain of my breaking heart when my marriage came apart thirty years later.

Track 3: “Faithless Love” is now a classic folk ballad covered by many artists since it was written and arranged for Linda Ronstadt by her first significant love and frequent artistic collaborator, John David Souther. His devout affection and undeterred respect for her is heard in every word and note of this song, and is echoed in the interview with him in Ronstadt’s documentary film. He passed away just a few weeks ago, leaving a legacy of hit songs he penned for Linda Ronstadt, The Eagles, and many of their Laurel Canyon contemporaries.

Track 4: “The Dark End of the Street” is a gorgeous track of secret love, or as co-songwriters, Chips Penn and Dan Moman described it, “the best cheating song ever.” The original was released by gospel-turned-R&B singer, James Carr, whose expressive voice cries out in equal parts soulful heartache and sinful remorse, in as compelling a narrative as any blues tune I’ve ever heard. Although my research can find no documentation to prove it, I write with as much certainty as I can trust my ears and my gut (which is pretty formidable when it comes to music) that the backing vocal voice on Carr’s recording is none other than gospel-turned-R&B living legend, Mavis Staples. Although I regarded Ronstadt as a country-folk artist when this album was released, her soulful arrangement of this song felt as pure to me then as any of the singles from the Staple Singers that were also treasured pieces of my 45 collection at that time.

Track 5: “Heart Like a Wheel” is another track that Ronstadt writes about in her memoir and talks about in her documentary as being a song that she became obsessed with recording, from the very first time she heard it performed by the McGarrigle Sisters while on tour in Montreal. This tragic folk song was written by Anna McGarrigle, a member of a family of prolific Canadian folk musicians. She recorded and released a version with her sister, Kate (the late wife of Loudon Wainwright III and mother of Rufus and Martha Wainwright) on their debut album, Kate and Anna McGarrigle. The McGarrigle Sisters hauntingly harmonize a tale of impossible love that can “wreck a human being and turn him inside out.” Their lyrics are paired with sparse instrumentation on the McGarrigles’ rendition, creating a Celtic folk sound and conjuring up visions of Cathy and Heathcliff in my mind. Linda Ronstadt’s adaptation pours out an equally heartfelt telling of this tragic love story, harmonizing with fellow Laurel Canyon songstress, Maria Muldaur, over a delicate string and piano arrangement. “Heart Like a Wheel” is quite simply one of the most breathtakingly beautiful songs I have ever heard.

Track 6: “When Will I be Loved” is the track most associated with Linda Ronstadt, although she had many number one songs on pop, rock, and country singles charts, this one only reached number two on the pop chart. Nonetheless it has endured as her signature track and was the centerpiece of her Rock & Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremony in 2014. This may be due to the feminist message it delivered to young women like my mom in 1974, a pivotal time in the Women’s Movement. The lyrics still resonate with the three generations of women who have come into adulthood since then. Ironically, the song was written by Phil Everly and released as a single in 1960 by The Everly Brothers, peaking at number eight on the pop charts. Again, a stunning example of Linda Ronstadt’s ability to interpret a songwriter’s work and to make it feel authentically her own, for her and for her listeners.

Track 7: “Willin'” tells the story of the 1970s American truck driver. I generally skipped over this track on the album as a child, it didn’t tell a story I could relate to at all then. When The Sound of My Voice documentary was released, my friend Laura told me that “Willin'” was her favorite Linda Ronstadt song. I revisited the track upon her sharing this with me. In 2019, “Willin'” brought me to tears, and to my knees. Not because I could relate to the life of a truck driver, but rather, the rigors of the road life in “Willin'” are remarkably relatable to the years I spent in the music industry and married to a tour manager. Because of Kris Kristofferson’s mastery for spinning “everyman” stories into song, I assumed he had written this tune. Upon hearing of his passing in June of this year, my first inclination was to listen to what I considered to be my favorite Kristofferson song. I was quite surprised to learn that “Willin'” was written by Mothers of Invention rhythm guitarist and Little Feat founder, Lowell George. I knew very little about this artist who wrote a large body of music in a short lifetime. Lowell George is one of those Southern California musicians whose life was ended abruptly in 1979 as a result of the prevalence of dangerous drugs in that culture during the 1970s.

Track 8: “I Can’t Help It if I’m Still in Love With You” peaked at number two on the country singles chart twice, in 1951 and again in 1974. According to a 2004 biography of Hank Williams, he wrote the song in the back of his sedan while touring across the country. While the song brought considerable notability to Williams in the 1950s, it delivered the Grammy for Best Female Vocal Performance to Linda Ronstadt in 1975. The song was beloved to her for its sentimental connections to her childhood, another similarity we share. Whenever I hear any Hank Williams song, my heart swells with sweet memories of my grandparents and their devotion to one another, and to their love of music and dancing. Her vocal approach is starkly different–deeper and richer, but its traditional country instrumentation, perfect two-step pace, and sweet harmonies with EmmyLou Harris were so authentic and charming that even Grandpa and Grandma delighted in this cover of one of their favorite tunes.

Track 9: “Keep Me From Blowin’ Away” is a lovely bluegrass tune first released by The Seldom Scene in 1973. Ronstadt’s rendering is reverent, with minimal variation from the original. Both versions are tender reminders of the gentler aspects of the folk-inspired music and artists that Mom admired in my early life.

Track 10: “You Can Close Your Eyes” was written by James Taylor and first released on his 1971 album, Mud-Slide Slim and The Blue Horizon. Taylor and Ronstadt are long-time collaborators and friends. Her arrangement gives more breadth and depth to the track than the signature stylings of James Taylor’s stripped-down voice and guitar approach. The lyrics reflect the friendships in the close community that existed in the lives of these musicians and their contemporaries…you can stay as long as you like…I can sing this song, and you can sing this song when I’m gone...When that day comes, (and I hope it is a long long time from now) I hope that James Taylor will remember to sing it in her honor.

Today, I honor Linda Ronstadt and celebrate the 50th anniversary of the release of Heart Like a Wheel with the most honest and earnest words I can find in my vocabulary. Below is a Spotify link to the album, Heart Like a Wheel. The second link is to a playlist I composed that includes the original and the Ronstadt recordings of each track, which I’ve been listening to fervently to write this Note. Long Live Linda ❤️🎶